"La legge dell'oca"

a web-searching rule

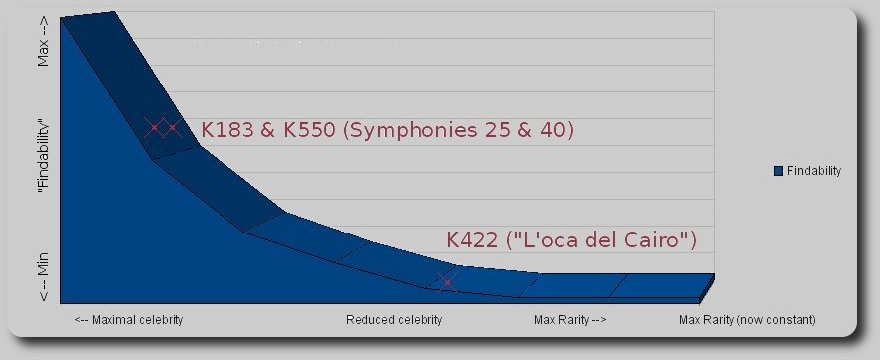

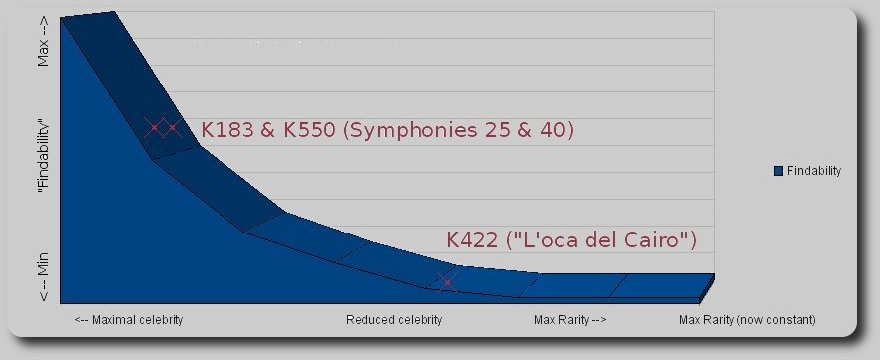

a demonstration of the direct relation between "findability" and "celebrity"

(by fravia+,

first published at searchlores in March 2008 - work in fieri)

|

|

|

|

Version 0.07:

March 2008

|

...have to thank you, together with my students, for your refreshing guide

to classical music searching (Laura Weingart, 6/03/2008)

Introduction

Ut queant laxis

resonare fibris,

Mira gestorum

famuli tuorum,

Solve polluti

labii reatum,

Sancte Ioannes

|

Today's searching session aims to demonstrate

the directly proportional relation that exist between a target "celebrity"

and its "findability".

While thinking about some

possible meaningful examples, I came out with the project of finding a "banal"

music piece and a "rare" music piece by a given renowned musical composer. .

Such intention seems indeed good, since for any given musical composer

there are indeed "masterpieces" and "minor works".

In fact the evolution of taste (or rather,

to use a more precise expression, the commercial

oriented "taste of the moment") dictates in a given timeframe

who are supposed to be the "great composers"

(some

"great" composers, held in high esteem during the past centuries,

are nowadays next to unknown -for instance Lully- while other now "famous" composers -

for instance Vivaldi and Mahler- have been rediscovered

after long periods of neglect). And the same "taste" force dictates

also which among their works

are to be considered "masterpieces" and which should be regarded instead as "minor attempts".

This means that for every "known" composer, we will have "celebrity" works that are

incredibly easy to find on the web, and less famous, "more obscure", works that

-if the "rule" we are checking holds true- should be more hard to find. As a consequence,

this searching

session could be titled "How to search for classical music" as well.

Our targets today will be works of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, the most enduringly popular

among classical composers... in fact,

the taste of this new beginning century regards Mozart

as THE composer par excellence. Among his works, some of the

Symphonies (3/4 movements: allegro-quick | adagio-slow |

evtl. minuet | allegro-fast) are among the

most well known pieces and have a very high degree of "celebrity".

Since almost every director did indeed try

his hand at Mozart's symphonies (often with dubious results), we will have to

filter the different performances, therefore,

while searching and checking, we will also

need to apply some evaluation approaches and

understand the different formats of the various files we are targeting on

the web through our searches

(in this specific case of course sound formats).

We will today throw our searching nets in the high seas of classical music, hoping

to learn a couple of searching tricks (underlined in the following

by a red bullet:  ).

).

Put on your seeker's

anorak, light your pipe and follow me in this trip.

Enjoy!

|

Mozart as a searching example

|

If we take Mozart as target composer, some "easy to find" works are immediately discernible:

among his 50-odd symphonies (or even more: the dividing line between serenades

and symphonies is blurred. Often, four movements out of a

serenade -that could have 8 or even 10 movements- were taken out and presented

as a "symphony". Some "symphonies" are therefore just "trasposed serenades")

he has composed only two symphonies in Sol minor (G minor) (# 25 K 183 and # 40 K 550).

Mozart's symphonies are numbered 1-41 from the order given in the Complete Edition -AMA-

published by Breitkopf & Härtel from 1879 to 1882. All Mozart's works are also

numbered with a K according to the Koechel

Catalogue. These two symphonies are

since centuries included

among his most important "masterpieces", probably because they have encountered

the "taste of the moment" -again and again-

for more than 200 years.

This incredible "permanent" modernity of Mozart's masterpieces

is probably due to the deep anxiety reflected in Mozart's music,

an anxiety that has become

the way of life in our consume oriented societies. Both symphonies, and especially symphony 40,

seem to reflect the deep sadness of Mozart's short life, and reach into our souls, connecting us

to a suffering that is a part of everyone's life, especially when a television set has been turned on.

Using both the G minor (sol minor) symphonies as our "easy" target, we can also check

any eventual difference in

the

"findability" of such easy targets among themselves:

the "great" G minor #40_K550 has always been (rightly)

considered as one of the absolute

masterpieces of

Mozart (to avoid confusion

we will ignore, in today session, the fact that there are

in fact TWO versions of the #40_K550, one with and one without the two clarinets),

while the "little" G minor, #25_K183, a "younger" composition, also one of the most

well-known Mozart's symphonies, is not

as "universally"

represented as her major sister.

Enough. We will use both symphonies #25 & #40 as "easy to find example":

they will be our first target today, the first blade of our scissor

Celebrity/Rarity. Roll up your sleeves.

Individuating a "hard to find" example is a much more complex task,

when dealing with a composer with Mozart's incredible "celebrity".

His works, even the most obscure have of course

been all digitized, and hence are surely bound to be found

at the end of the query.

Knowing that

a web-target MUST be findable somewhere is indeed

a reassuring knowledge. When searching instead -say- a Turkish poem of the fifties, you are

never sure if a digitized copy already exist at all on the web:

even your best search-strategies

could crush against the cliffs of nothingness.

"L'oca del Cairo" (K 422), an unfinished rare opera

I was able to hear

in Venice a couple of years ago, could -I hope- cut the mustard.

Mozart wrote "L'oca" in 1783, at age 27, and this work,

only rarely put on scene,

could represent our

"hard to find" target, so we could use it today as second blade of our scissor

Celebrity/Rarity.

Besides, this unfinished opera contains a wondrous duetto (Chichibio/Auretta) that

even the "taste of the moment" might appreciate nowadays ("Il padrone e' gia' sortito,

Il Marchese non c'e' più"). Enough: K422, "L'oca del Cairo"

will be the "hard target" we'll try to find today.

Doing this exercise we will be able to confirm (or maybe deny) that on the web

there exists

a directly proportional relation between "celebrity" and "findability" of a target.

Our searching endeavor will also show us how to capture streams, change sound formats and illustrate

some other

"must know" tricks that all searchers need to know when trailing against commercial wind on choppy web seas.

So we have now our targets: a "easy to find" target (both Symphonies #25_K183 and #40_K550) and a "hard

to find" target ("L'oca del Cairo" K_422). Let's find them and check if the "legge dell'oca" will hold true.

We should also remember that the quality might vary

quite a lot for each musical execution: there are DOZENS of interpretations: depending from its

directors, interpreters, musicians and singers, the execution of a same work can be

dire or sublime. So we will have tu fullfill an evaluation task as well.

How do we find out which are the BEST interpretations of our targets?

First of all we could trail the web for specific comparisons. Here for instance a comparison

between Bernstein

and Bohms directions of our

#25_K183 (scroll down half a page once in the link). But this kind of

approach would be very slow and noisy.

Here a query-attempt: "Mozart's symphonies"

("recorded by" OR "performed by") that will let readers find further

comparisons, for instance when discussing the quality of

Marriner's execution:

"The first half-dozen symphonies are as well played and as elegantly conducted,

but compared with the depths of Furtwaengler's mysticism, the heights

of Walter's lyricism, the weight of Klemperer's gravity, or the warmth

of Boehm's humanity, they may ultimately seem less satisfying. Still, Furtwaengler,

Walter, Klemperer, and Boehm rarely led the first three-dozen symphonies, leaving

the field open to Marriner". A lot of hints, it remains to be seen if such hints are valid, though.

Following this kind of approaches you could establish a

list of quality performers. But note how useful for our search relevant

readers' comments

can be  :

I found a comment by an amazon American user so helpful that I have

reprinted it below verbatim. It's excellent reading, if a tag preposterous:

it is hard to find

on the web other comments discussing with such depth the

different interpretations for EACH Mozart's symphony.

:

I found a comment by an amazon American user so helpful that I have

reprinted it below verbatim. It's excellent reading, if a tag preposterous:

it is hard to find

on the web other comments discussing with such depth the

different interpretations for EACH Mozart's symphony.

Relevant usenet discussion groups can also be very useful

for evaluating purposes. Moreover you can

quickly and effectively peruse them  .

.

But, as said, reconstructing the constellation of best interpretations through single comparisons is

a slow and noisy searchwork. Fortunately

there are also some tools we can use as integration: for instance this

Archivmusic

database (sellers of classical CD in the States)

will present us his list of Conductors, Ensembles and Labels for our

#25_K183

and

#40_K550.

Also very useful (astonishing enough for those of us that have ever despised such kind of sites)

is answers.com,  that will give us an almost integrale list of all albums that carry a complete performance of our targets with DATE.

Truly a treasure mine of searching angles.

that will give us an almost integrale list of all albums that carry a complete performance of our targets with DATE.

Truly a treasure mine of searching angles.

Of course I do not pretend that you perform

this (necessary) evaluation work onto today's targets, that are intended just as

search-examples. You'll do this kind of

in depth "evaluation scanning"

by yourself when searching for targets that specifically interest you.

"No one can better search your own targets than you yourself" used to say the older seekers.

Just keep in mind that

searchers should always have gathered some sound and helpful evaluation material

already BEFORE starting their queries.

You can use the following short list of interpreters (conductors) of Mozart's symphonies

that I have already compiled to finetune by yourself today's query, thus

realizing

some of the complexities of this specific search-task.

Given the fact that almost

every conductor in the world

did indeed try his hand at these Mozart's symphonies (often with

dubious results), we have a

choice among much too many performances. I have listed only those that

seem to have been

considered by critics

"the best" (of course such considerations are always biased

in matters like "interpretation styles"). Here you are:

-

Claudio Abbado,

Mozart: Symphony 25 & 31; Masonic Funeral Music; Posthorn Sym. (Sony, Berliner Philarmoniker) and Claudio

Abbado, Mozart: Symphonien No 40 & No 41 "Jupiter" (deutsche Grammophon, London Symphony Orchestra)

-

Otto Ackermann, Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra (Concert Hall Society), 1952-1955 (hard to find edition)

-

Sir Thomas

Beecham, pre-war (better):

London Philharmonic Orchestra, Abbey Road Studio No. 1, London

1937 - post-war: Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, #40_K550, 1954, Walthamstow Town Hall

-

Leonard Bernstein (Vienna Philharmonic 1984-1986,

both our easy targets in the

Deutsche Grammophon - 474 349)

-

Karl

Bohm (Berlin Philharmonic Orch., 1960: 40 & 41, 1969-1999: other symph.). There is also a "Vienna" (not

Berlin) edition.

-

Adam

Fischer (SACD recordings, april 2007 Danish Radio Sinfonietta)

-

Hans Graf, Mozarteum orch., Salzburg "CAPRICCIO", 1980-1999

-

Nikolaus

Harnoncourt Concentus Musicus Wien, rec. Dec 1999 and Dec 2000 in the Kasino Zoegernitz, Vienna

-

Christopher

Hogwood (#25_K183 he will direct in the Symphony Hall in Boston, USA, Friday 7 March 2008 @ 20.00 and

Sunday 9 March @ 19.30 (Handel and Haydn Society) - #40_K550: 1986 Academy

of Ancient Music)

-

István

Kertész(Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra - Sofiensaal, Vienna, November 1972)

-

Otto

Klemperer (EMI & Testament).

-

Concertgebouw Orch. of

Amsterdam (rec. 1972). Complete

edition together with Marriner (Marriner = early symphonies).

-

Erich Leinsdorf (Royal Philartmonic Orch, hard to find edition)

-

Peter Maag (#25_K183: RAI orch., Rome - #40_K550: Orch. di Padova e del Veneto)

-

Sir Charles

Mackerras (Prague Chamber Orch., Scottish Chamber Orch.) Telarc, 2003. (There is also a VERY recent

re-edition of the #40_K550 with the Scottish Chamber Orch:

25 february 2008. Alas,

I haven't found it -yet- on the web)

-

Neville

Marriner (Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, around 1970). Complete

edition together with Krips (Krips = late symphonies).

-

Trevor

Pinnock, the English Concert, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Orch., Archiv, "period instruments" performances, 1992-1995

-

George

Szell (Severance Hall, Cleveland orch.)

-

Jaap Ter Linden, Mozart Akademie Amsterdam,

"Brilliant" edition. In fact the interpretation I myself prefer, at least for our #25_K183 target.

-

Bruno

Walter (#25_K183: 1954, mono, New York Philharmonic - #40_K550: 1956, stereo, Columbia Symphony Orch.).

Also a BBC edition.

Now we can begin our queries, using the list above for evaluation and filtering purposes whenever we will

pull off the web

our nets full of zapping results.

|

The easy target: Finding 2 well known symphonies

|

Mozart composed 50-odd symphonies, most of them (around forty) when he was very young.

The K183 (Symphony #25, "tan-taran-tantinera...") is the "little" G/sol minor,

one of only two in G/sol minor (whereas a good half of Mozart's

symphonies are in re major), and hence

directly connected with her "great" G/sol minor sister: the

later K550 (Symphony #40 "tiritin-tiritin-tiritina...").

Just to wet your appetite (this is after all a trip into classic music as well as a trip

into searching):

the most original part of #25_K183 is

the almost "beethovenian" and mysterious Andante (second movement)

while the most interesting part

of #40_K550 is the famous Menuetto (third movement),

that Toscanini considered the "most tragic piece ever written".

It is worth recalling that symphony #40_K550 is the most

renowned and esteemed among these two "celebrities",

and became so ubiquitous to be

considered -together with the serenade

Eine kleine Nachtmusik (K525) the very

"musical footprint" of Mozart.

Now we will begin our search. What do we want? We want

K183 and K550, we want FIRST the music,

and with this I mean good quality, not just the first one stale mp3

we will find. Ideally we want the

whole palette

of the

best interpretations ever made on our planet.

As SECOND element

we should strive to find the scores of our musical targets...

in case we want to better follow or even to

play ourselves... and maybe interpretate the music on our own :-)

First attempt

OK, we don't need to gather that many searching "angles": the queries, for such simple searches,

will of course result very simple themselves.

Let's begin with

an elementary search when dealing with music nowasays, often used just to

quickly check what's globally "flowing

around" on the web:

http://www.youtube.com/results?search_query=K183&search_type=.

We get various results, as expected. We need now to apply some

quick evaluation skills to filter out crap. Note how

negative evaluation rules are much easier to implement than positive evaluation rules.

We avoid at once the first result

because of evident incompetence: the picture related to this tube does not

even represent Amadeus Mozart,

but his

father Leopold. Whomever uploaded this doesn't understand zilch. Begone.

The second result

is called "ukulele" Mozart (sic), so we ditch it immediately as well. Good riddance,

whatever it might have been.

The third result seems promising: this is a very famous interpretation of the "Allegro con Brio"

first movement

by Karl Bohm, a Mozart expert of

the sixties, that

registered last century

the full cycle of Mozart's symphonies conducting the Berlin Philharmonic.

So quality is there... and we might take the opportunity

to hear right now the famous

Andante of our "little" easy

target.

Since the Menuetto

and the

Allegro are there

as well, and since our second "great" easy target (K550, symphony 40) is

on youtube as

well, even accompanied by some Bernstein's lessons,

(with the Wiener Philarmonic!)

about its interpretation intricacies,

our "easy" searching task could seem already completed,

but in fact it isn't completed at all.

We have barely started.

The low quality of a streamed youtube

music snippet is next to ludicrous. Seekers should try to reach perfection, and

strive to satisfy even the

most prickly audiophiles: let's therefore look for better formats

for our targets.

Second attempt

"K 183" OR "K183" OR "symphony*25"

This is a simple, yet solid search-arrow. Note the asterisk because we don't know

if there will be a "N°", "N.", or nothing at all before

the number.

As you can see google gives rightly wikipedia as

first answer: we can use wikipedia at once

in order to find our first

score for #25_K183

...not that Mozart's most famous

works' scores were

particularly difficult

to find on the web, despite all kind of pressure by the bastard commercial idiots

against nice people that only wanted to spread knowledge.

Censorships attempts at scores are particularly ludicrous and anti-historical,

since the (correct)

trend is to go more and more

on line with all classical music scores of the world for free.

For Mozart we should specifically take advantage of the very

good NMA (Neue Mozart Ausgabe digitized

by the international stiftung Mozarteum).

Just input the K number (for today's session: 183 or 550)

and retrieve the scores you need. I am sure that, were not for the backward fights of the

stupid patent holders, we would nowadays all been able to fetch directly

and immediately not only the scores

but also

THE MUSIC we wanted, from any composer, from any director, in lossless

format (well, we will get it anyway, after all :-)

Don't get me started on patents: why should a music student from -say- Africa, that lives

on a budget of few euros a month, be deprived from the joy to play

(or enjoy a good edition of)

the Sol minor symphonies (or whatever else Mozart wrote)?

Mozart didn't patent his works after all, bastard patent holders!

There, I said it again. Enough.

Another side-benefit of this kind of "broad" searches

is that we can almost always find in our searching nets, together with the music,

some scholar "lessons" about our targets, and various

interesting

material.

Suffice a simple pdf

query  (incidentally the same query will give us also

plenty of opportunities to fetch another free

score for

#40_K550).

(incidentally the same query will give us also

plenty of opportunities to fetch another free

score for

#40_K550).

Of course if you are interested in books (and you should, about any target) you better always begin your search

visiting both the relevant parts of

Project Gutemberg and of

google

books (&as_brr=1, full view, to catch books un the public domain

and &as_brr=0, all books, patented or not, VERY useful to find relevant

snippets and gather angles for further searches)  .

.

Let's refine the query above, eliminating some commercial crap:

|

K183 | symphony-*-25 "K 183 " -site:.com

While still extremely simple, this is after all not so bad a query, judging from the results.

Pruning com sites is very often very useful to lower noise on the web.

In fact we can now begin to gather some mp3s. The first beef of this session.

Two caveats about our present and future results: the first and most important

caveat regards bitrates,

the second, far less important, regards patents (i.e.

copyrights):

-

FORMATS: The most used 128 kbit/s bitrate, while common,

is barely acceptable for audiophiles: note that lossless uncompressed

audio quality snippets, FLAC or physical CDs, usually carry bitrates above 1,400 kbit/s.

Nowadays a bitrate of

192/44 is more and more used for mp3.

Your mp3s should at least have the 192/44 minimum

(250 or 320 kbit/s would be even better).

-

PATENTS: We will find on the web some music snippets that might be, in some country,

subjected to the usual -and rather

silly- patents or

copyrights laws. Though I hate copyright enforcers, that I consider enemies of knowledge and

hence low life forms,

I don't condone violating laws.

The material you can find on the web is usually in the public domain,

however sometime it can be

of rather dubious provenience. This applies to the results of today's searching session

as well. If in

doubt,

simply DO NOT DOWNLOAD the stuff we will find,

especially if your country (or if the country of the

proxy you are using)

is subjected to copyrights and patents enforcing laws

(not all countries have signed the relative conventions,

if you live in -say- S.Marino, you can happily

ignore patents and copyrights).

Once again: in case of doubt, just do not download the target files,

just hear the

music on line without burdening your hard disk and do not worry in the least:

since you are (to become) a good searcher, you will never need to

hoard stuff on your harddisks, you will always be able to find again in a few seconds

whatever you want to hear, see, read or

use, fetching it on the fly from somewhere on line.

Using the anticommercial query listed above we find both our easy targets, in mp3 format,

at once:

here the -I suppose in the public domain- first

movement of our #25_K183 (Allegro con Brio) in a good 192/44 bitrate

for a conspicuous, 10.2 megabytes long,

mp3:

http://kata.ro/index.php?search=allegro&page=53.

Alas! The quality simply isn't inside there:

this 7:23 long "Allegro con Brio" of the "little" target, as you can see, carries

no information whatsoever about director and

orchestra. Has only the tag "MOZART EFFECTS III - INTELLIGENCE" which is probably a

reference to volume III "Mozart in Motion"

("best used during times you want to accelerate your creativity" sic)

from the baloney American

theory

that listening to Mozart can increase newborns' intelligence.

We might as well use the same link's search facility

to download a 128/44 bitrate, probably in the public domain as well,

7 megabytes long snippet of our target

#40_K550,

again, no information whatsoever about director and

orchestra. Tssch.

There's another 7:49 long 182/44 "Amadeus soundtrack"

#25_K183 MP3,

no indications, but if it is the soundtrack of the film "Amadeus",

it must be conducted by Marriner.

Finally I will add the

10:14 long, bitrate

192/44 #40_K550 second movement andante from the

same source. Just to let you have a small taste of the real Andante.

Enough. Let's simply take note, for our searching exercise, of the incredible

quantity of #25_K183s and #40_K550s MP3s that float around the web. It's a celebrity, it is easy

to find.

Quod erat demonstrandum.

So so. "Have mp3s, any mp3s, will travel"? Have we searched enough, did we dig in depth? Nope.

That's a poor catch of dubious quality, unworthy of a seeker.

The searching process and its phases

|

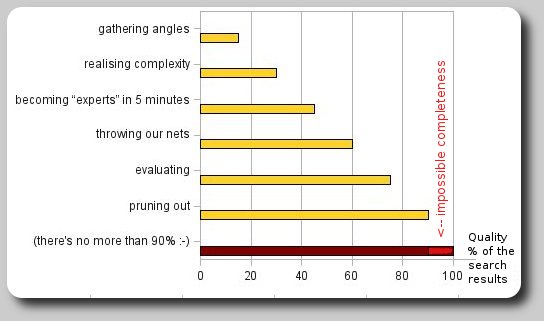

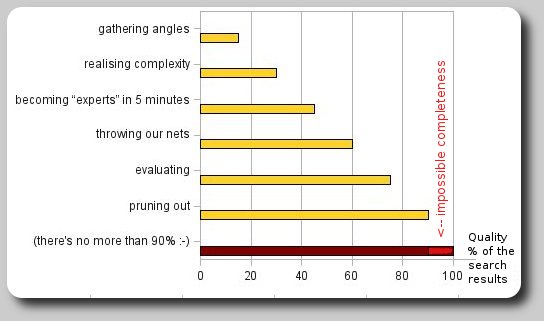

Let's see if we can find better stuff. We are almost halfway in what I would describe as our "searching process".

Whenever we begin trailing the web for a target, we go through a series of equally important searching phases:

gathering our searching angles in order to start our query with a quiver full of

correct terms,

realising the complexity (or to be more precise, the complexities) of our task, which will

allow us to gather even more angles and to finetune our searches,

becoming

experts (well, "sortof" experts, take this cum grano salis)

on matters that we didn't necessarily master 5 minutes before. We began to walk

on the right paths, but

there's still much to do.

We must now prepare

our wider nets and then we will have to

carefully evaluate the

results we will gather

and without pity prune them out, throwing away all those small, zapping, results

and keeping only the juicy sound, high

quality, ones. And we will have always to keep in mind that there is noway to find all

relevant results that may indeed exist on the web. Whatever search strategies we might use, some parts

of the web will not be trailed by us and we will never gather a really "complete" catch (this "impossible

completeness" is another

law of searching that would deserve a nicer name).

| |

|

Preparing our wider nets

Let's try a "wider" search:

"(zip OR rar)

("music mozart" OR "music classical mozart " OR "music classic mozart")

What have we done here?

- we presumed that whomever might offer our target has some logic

directory structure we can maybe guess

.

.

- we presumed that our targets will NOT necessarily be in MP3s but rather in a

zipped "zip" or "rar" file format (in fact you could add the whole list:

gz, ace, and so on)

.

.

In fact the results are quite interesting: As you can see we can for instance

now at once gather (or just simply hear on the fly) some MP3 collections, ripped from Trevor Pinnock's

edition with a decent

192/44 bitrate, that contain all four movements

of our target

#25_K183 (it's inside Pinnock's disk 7, so we get as

an added bonus also symphonies #24_K182, #30_K202 and #31_K297 "Pariser").

Ditto for our second "simple" target #50_K550: it's easy to find, inside disk 11, together with the

equally

famous Symphony #41_K551 "Jupiter". And we are not limited to Pinnock. Examining the results of the

previous query you'll quickly find a link to Carl Bohm & the Berliner Philharmoniker's

#40_K550 (coupled together with Symphonies #39 and #41) which comes along

in a very good 256/44 bitrate edition and could actually satisfy minor searchers.

Let's see now a "dedicated search", and check -say- if we can find our first target directed by the

first item in our "directors' list" above:

so we do want a nice #25_K183 under

Abbado direction? It's there! Harnoncourt? Yessir! Bohm? Of course!

Well, I fear that our searching studies are after all overkill

for such an easy target. Even with an extremely

simple

& banal query we land smack in signal_zone.

Just filter the results nationally and

keep only countries that seem less obsessed by copyrights  :-) Quod

erat demonstrandum: "facilia" abundant in tela.

:-) Quod

erat demonstrandum: "facilia" abundant in tela.

Least but not last, we might as well prune this bunch of results in order to gather

"The Cambridge Mozart Encyclopedia" by Cliff

Eisen & Simon Keefe,

Cambridge University Press (ISBN 0521856590), January 2006, that -judging from its

frequency on the web- seems to have been now released in the public

domain. In doubt, we wont download it. Let's just consult it on the fly

and use it at once in order to check back on our own three targets, thus gathering

more angles and more "expert" knowledge. This "further refining as you progress" is a

common practice when searching and is particularly important

for long term searching exercises  .

Our "G minor" searchlavine is rolling down the webhills: go go go!

.

Our "G minor" searchlavine is rolling down the webhills: go go go!

Some alternative searching approaches

A possible, if rather haphazardous, search alternative would be to comb the web for

radio stations  that might allow us to

download our target snippets. As an example, check one of the most famous stations: the

danish radio

station, where you can regularly download

some fairly good editions of classical music (today they offered

for instance the second symphony of Beethoven). Our #40_K550 target was

for instance on offer for free

some time ago.

that might allow us to

download our target snippets. As an example, check one of the most famous stations: the

danish radio

station, where you can regularly download

some fairly good editions of classical music (today they offered

for instance the second symphony of Beethoven). Our #40_K550 target was

for instance on offer for free

some time ago.

Alternatively, if you are using GNU/Linux, point streamtuner

(after having installed streamripper) to the "classic" tag and look for your own

targets among the many

stations listed... with easy targets like ours,

chances are that some station, somewhere, is sending out Mozart's symphonies right now :-)

The wealth of stations offering music for free on the wev is astonishing  .

.

However, be aware of the fact that for all radio station the maximum bitrate is usually just 128.

Another approach in order to limit the scope of your searches

is to find, and listen to, the snippets proposed by on-line sellers and re-sellers, for instance

Barnes&Noble,

such an approach enables you to quickly judge if a given target is -at all- worth to buy (or -rather-

if it is worth download

elsewhere for free)  .

.

A further possible approach is the [messageboards|forum|webrings|specific

dedicated sites] approach  .

I will give only a couple of examples, you can easily find more: in

order to find all possible "messageboardish" targets, just comb

the web or visit the usenet galaxies.

.

I will give only a couple of examples, you can easily find more: in

order to find all possible "messageboardish" targets, just comb

the web or visit the usenet galaxies.

• •

Be aware of the fact, however, that some messageboards (for instance

The Mozart Cafe) are

next to useless in a web where stale sites abound. It is important to know

how to quickly skip all non-promising results. Negative evaluation

rules apply in this context (again)  . .

|

• • The BBC third channel has a couple of messageboards:

"CD

review" and "Performance". In the European

Union you can in fact "go shopping" for "third" radio channels dedicated to classical music,

that you will find in almost all member states, even the smallest, for instance:

be

(click on "ecouter en direct"), ie (listen

live) and

dk

.

The huge advantage with classical public or national channels, is that they still (at least in part)

views their listeners as citizens seeking knowledge

and not just as consumers of the product on offer. The disadvantage, is that such an approach is very

time consuming and should be used only for "long term" searching

purposes. .

The huge advantage with classical public or national channels, is that they still (at least in part)

views their listeners as citizens seeking knowledge

and not just as consumers of the product on offer. The disadvantage, is that such an approach is very

time consuming and should be used only for "long term" searching

purposes.

|

• • When searching messageboards that may carry links to

music files, it is worth remembering that

some of the most useful are in

far away countries

.

Some time ago "The Economist classificated

the piracy

levels in different countries: these data are instructive for searchers.

Note that

almost all main search engines can be limited to results

pertaining only to specific country codes (e.g., in google, the

parameter &cr=countryID

means "only Indonesia"). .

Some time ago "The Economist classificated

the piracy

levels in different countries: these data are instructive for searchers.

Note that

almost all main search engines can be limited to results

pertaining only to specific country codes (e.g., in google, the

parameter &cr=countryID

means "only Indonesia").

Do not underestimate this kind of regional searching:

One could for instance quickly find

Ter Linden's (good)

execution of our #40_K550

through some specific

"audio search engines" (at acceptable

rates: 256/44 mp3s, I=13.7MB, II=18.1MB, III=7MB, IV=12,9MB).

|

On usenet, the most important groups are

rec . music . classical

rec . music . classical. recordings

There is a HUGE wealth of comments and information to be combed here. A "must visit" stop for this kind of searches.

Some specific "dedicated sites" can result useful as well:

• •

http://www.mozartforum.com/ has a collection

of short articles

in its library.

• •

Also the "musical settings" of both symphonies

can be seen in a

graphical display, courtesy of www.studio-mozart.com,

a awful cookies & flash obsessed site:

183

and

550

|

Finally it is worth underlining the importance of going regional with our

searches, which means, to seek information and targets in other languages, not only English. Note

that you don't really necessarily need to know these languages to find your way  .

.

Here an example: "symphonie en sol mineur" 550.

As you can see, once you go regional the searchscape changes dramatically, and you can find useful

findings like this complete list

(in french) of the "Brilliant" edition (120 pages).

Note that you can (and should) repeat the search for any relevant language, for instance

550 sinfonie "g moll"

filetype:pdf will quickly give you another nice

score

for the "great" sol minor Symphonie.

While in today's session our targets are so easy to find that such "regionalisation"

is not really necessary,

in so doing we can still find

little jewels like the wondrous snippet from George De Saint-Foix (written in

the late thirties of

last century), that describes (in French) the beauty of the "great" sol minor #40_K550.

If you understand French, is it by all means instructive to follow

the music we found with this text in your hands.

Third attempt

Our easy searching task would seem completed, but in fact it isn't completed at all.

We have barely touched the "good" results.

We have to find our "easy targets" 25_K183 & 40_K550

in a good music format, i.e.

a LOSSLESS,

uncompressed format, which means flac (the best one)

or Monkey (APE) or wav, we cannot be satisfied

with a compressed format like MP3, AAC, or Vorbis. That's good for the car-stereo while concentrating on

something else, but won't help any serious understanding of

the nuances of Mozart's music.

We might try a first "brutal"

approach: mozart

symphonies flac

Yes, it works, but it is not very elegant, is it?

Let's see if we can do better, it's often just a matter of filtering out the crap  :

:

mozart

40 550 (flac OR ape) -"your cart" -store: Bum! Harnoncourt,

Schwarz, Pinnock, Mackerras, Levine, Kraus, you name the director...

Repeat for #25_K183: mozart

25 183 (flac OR ape) -"your cart" -store

Yep, as the results of the previous search underline: maybe slightly (slightly!) less web-present than the "great" G minor sister, but

quite easy to find as well...

...Quod erat demonstrandum.

So we have found both our targets, directed by a palette of (hopefully) good directors. We have of course

also

found the scores of both targets and, nebenbei, we have even gathered some interesting texts and books about

mozart and his works. Our approach was instructive I hope, and the search was easy. Let's see how easy it is to find

a less famous target, let's see if the direct relation between "celebrity" and "findability on the web" holds

true.

|

The hard target: Finding "L'Oca del Cairo"

|

Let's begin our "hard" search. What do we want? We want "L'oca del Cairo",

K422, we want

the music... if possible various choices

of the

best interpretations ever made, AND the libretto, if possible with a

translation in English for those among us that do

not understand Italian, AND the score...

in case we want to play "l'oca" ourselves... and maybe interpretate and/or sing it better :-)

Let's see what "angles" we already have for our query (or what

angles we can rapidly find out, for instance through the long description inside the

Cambridge Mozart Encyclopedia we have found before, or

more simply through

good ole

wikipedia):

-

"Oca del Cairo"

-

"K422" OR "K 422"

-

varesco

-

Pippo, Pantea,

Celidora,

Biondello,

Calandrino,

Lavina,

Chichibio,

Auretta

-

"Ogni momento dicon le donne" / "Le perrucche di Strigonia"

Looks like a simple search, doesn't it?

Let's try a diagonal approach: "le

perrucche di strigonia"

A small typo will help us distinguish between two versions. Note how typos

are VERY USEFUL to differentiate "families" of results  :

:

+"strigonia"

+"la camicie a centinaia"

+"strigonia"

+"le camicie a centinaia"

Ah, here we have a complete version of the

libretto, not just a couple of scenes from the first act.

Of course we can always fetch both libretto and score from the

:NEUE MOZART AUSGABE. A possible alternative

for "libretti" is Public-Domain

Opera Libretti and Other Vocal Texts at Stanford.

So we have the libretto(s),

let's begin our musical search: can we just start "from the bottom" of our previous searches and see if we can

find our Oca at once in flac format?

mozart 422 (flac OR ape) -"your cart" -store

Not yet! We are also hampered by the noise due to Krip's "Philips 422 476-2" disk.

Noise due to haphazardous similarities (there are many kinds of typos, some even "on purpose", see

adnominatio, metonimy, human malapropism and paronomasia)

can sometime be a great ostacle when searching  .

Let's eliminate it:

.

Let's eliminate it:

-Philips +mozart +422 +(flac OR ape) -"your cart" -store

Now the water is more clear.

We can see that in the "Complete Mozart Edition ", by Decca, there are various versions of

the Oca conducted by Peter Schreier.

There is a "Disk6", a "Disk39" and a

"Disk 9" of "Box 14", all referring to the "Middle Italian Operas" collection:

"L'oca del Cairo, K.422 Reconstructed by E. Smith"

Inga Nielsen (vocals), Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (vocals), Douglas Johnson (vocals),

Edith Wiens (vocals), Christine Schornsheim (harpsichord), Anton Scharinger (vocals),

Pamela Coburn (vocals), Berlin Radio Symphony Chorus (choir, chorus),

Chamber Orchestra "Carl Philipp Emmanuel Bach",

Peter Schreier (conductor) (Together with "L'oca" you'll find in these disks

also Mozart's K_430

"Lo sposo deluso")

Let's try to clear this mess a little using

arkivmusic.

It seems that we have -

A "Complete Mozart Edition 14 - Middle Italian Operas" (2006), 9 disks, Philips

Complete Edition Box 14:

Middle Italian Operas (9 CDs), The Oca being inside CD 6

-

A "Complete Mozart Edition Vol 39" (1991) Philips

Conductor: P. Schreier (Disk 39): Mozart -

L'oca del Cairo - Anton Scharinger - bass | Inga Nielsen - soprano | Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau - baritone

| Douglas Johnson - tenor

-

A "Hans Rotman edition" (1999) Cpo

Hans Rotman

Antwerp Chamber Opera Orchestra (Orchestra), Herman Bekaert (Performer), Bernhard Loonen (Performer)

-

A "Mozart 22 - The Complete Operas" (2007) Deutsche Grammophon DVD series, from

the 2006 Salzburg Festival. This huge collection contains

a DVD that is also sold independently alone: DVD

"Camerata Salzburg" edition (2007), with a version from the Salzburger festival,

Conductor: Michael Hofstetter, prepared

by director Joachim Schloemer

and the Camerata Salzburg, but we

will ignore it and don't search anything related since Schloemer

has added "prerecorded dog barking and yiping that interrupts the music". You see -once more-

how useful users' comments are

in order to avoid similar crap.

Gee, only three editions: Schreier, Rotman and Hofstetter/Schloemer!

The strange thing is that

according to some links L'oca del Cairo seems to be inside disk 6 and not inside disk 9.

I thought that this was just confusion,

due to the fact that there are 9 disks in Schreier "box 14", but in fact it dovetails

with one image found on the web,

where we can clearly see the number "9" on the Oca del Cairo disk. As we will discover, this is

quite relevant in order to finally find this opera.

Let's finetune our search onto our three possible paths:

going deeper

Yep, there's some signal in here, but a lot of noise too.

Let's try the other edition:

39 complete.mozart "oca del cairo"... ahh, much better, more promising.

What about the Rotman edition?

"rotman" "oca del cairo",

nope, does not seem to give much signal.

Proceeding from the searchstrings above, I could finally find our target (only in flac format!)

using the following "strange" searchstring:

"box 14" CD9.

This proves, once more, than you don't really need extra complex searchstrings,

once having taken the time

to delve a little inside the different "aspects"

that your target's definition (in fact its "name")

can assume on the web  .

.

Now, AFTERWARDS, it is easy to see that from the beginning we got less noise just having added

the term "FLAC" to our musical searching queries. Hindsight is always 20/20.

A related observation: When we were searching for our Mozart's symphonies in G minor,

we could find tons of mp3s relating to

each and every symphony of Mozart. For "L'oca", however, this simply isn't true.

See,

the problem with such "rare" musical targets is that no one bothered

to put specific

mp3s on line, if we find L'oca, is just because it is contained in some "complete collections"

of the Author. In this case, being the author Mozart, there are several editions of

such collections floating

around: this

completely confirm our "legge dell'oca": there is a direct relation between celebrity and

findability. Quod erat demonstrandum (I'm saying this for the fourth and last time: we have finished).

What have we done today?

We have confirmed a web searching law, and

we gathered every target we wanted, just following some of the simple google

links we tried today (gosh we didn't even need to use any

other of the main search engines, nor to really go

regional, nor

to visit usenet). All this was probably overkill anyway :-(

I simply gathered and continued to search until I had

at least one lossless format for each target. Then I stopped. Therefore I did not

gather some "important" editions (for instance directors

George Szell or Bruno Walter) that of course are on the web as well. This will be left

as an exercise for the reader.

I will not give below (one never knows, in the current patent-paranoia climate)

direct links to material that could not belong

to the public domain (where it should belong). In doubt, hear the

music on line. As said, respect the laws of your country

of residence, or of the countries of the proxies you use.

Links'nature is in any case rather ephemere, while for seekers links are

quite

superfluous: we have cosmic power... once you know how to search,

you will find whatever, whenever,

wherever it may have been linked away.

Here follows the "beef": every one of these different

versions of our targets (and of course much more) can be found just studying this

essay, exactly as I found them.

-

Symphony 25 (K183) by Abbado: wma_Losless,

Allegro con brio 52MB, Andante 19MB, Menuetto 12,5MB, Allegro 33,6MB

-

Symphony 25 (K183) by Jaap Ter Linden: MP3 320/44,

Allegro con brio 25,3MB, Andante 14MB, Menuetto 7,7MB, Allegro 16,7MB

-

Symphony 25 (K183) by Pinnock: MP3 192/44,

Allegro con brio 14MB, Andante 9,4MB, Menuetto/Trio 5,7MB, Allegro 9MB

-

Symphony 25 (K183) by Marriner: MP3 192/44,

Allegro con brio 10,6MB, Andante 5,7MB, Menuetto 5MB, Allegro 6,4MB

-

Symphony 25 (K183):

score

-

Symphony 40 (K550) by Krips: Flac: perfect format.

-

Symphony 40 (K550) by Bohm: MP3 256/44,

Molto Allegro 15,4MB, Andante 14,8MB, Menuetto/Allegretto/Trio 8,7MB, Allegro assai 9,5MB

-

Symphony 40 (K550) by Pinnock: MP3 192/44,

Molto Allegro 10,2MB, Andante 15,6MB, Menuetto/Allegretto/Trio 6,6MB, Allegro assai 13MB

-

Symphony 40 (K550) by Harnoncourt: MP3 192/44,

Molto Allegro 9,1MB, Andante 14,8MB, Menuetto/Allegretto/Trio 5,3MB, Allegro assai 12,4MB

-

Symphony 40 (K550), scores:

(Erste Fassung)

(Zweite Fassung)

-

L'oca del Cairo (K422) by Schreier (Box14CD9): Flac: perfect format.

-

L'oca del Cairo (K422): Libretto (complete)

version 1

-

L'oca del Cairo (K422): Libretto (complete version with score)

Neumann 1960

-

We also had the opportunity to consult

on the fly "The Cambridge Mozart Encyclopedia" by Cliff Eisen & Simon Keefe,

Cambridge University Press (ISBN 0521856590, 2006) and we did gather

some other interesting background material in pdf format.

What did we find NOT?

Nothing there's nothing we didn't find, I even found a copy of the libretto of K422 in English

(I found one in

Spanish, as well).

Yet the english version of the libretto of K422 was not easy to find. Not at all.

So I wont link to it. It

could in fact be a task where those that had the patience to read until

here could apply their (hopefully improved) searching skills :-)

So did we prove the "Legge dell'Oca"? Is there a real direct relation between "findability" and

"celebrity" of a target? Indeed there is, as those readers that took the time to follow the links we

have used in this essay will surely have noticed. But we also determined

that the "findability" curve

never vanish: rare and obscure subjects are surely more difficult to find than

ubiquitous targets like Mozart's "great" G minor symphony K_550, yet even such

rare targets ARE lurking somewhere in the deep deep web. So

even

when approaching maximum rarity levels the chances to find a

given "rare" target remain constant  .

.

It was a good catch, tired after we had to delve with the commercial web-morasses

we may now rest, unzip our seekers' anoraks and take our wet boots off,

taste a glass of good Porto,

alight a small fire in the chimney and listen carefully to

the wondrous duetto between Auretta and Chichibio, in "L'oca del Cairo":

"Il padrone e' gia' sortito,

Il Marchese non c'e' più", or wonder about the various versions

of the

strange "beethovenian" Andante of #25_K183...

How comes I prefer Jaap Ter Linden to Abbado, Pinnock and Marriner?

Reviews:

Classical CD Rebiew, check index of

composers

Classical Inkpot ("proudly made in Singapore"), for instance for

#40_K550

Classics today, tons of reviews

Music web, Uk site. For instance, for #40_K550

zweitausendeins use "suchen" in order to search.

Best interpreters for all Mozart's symphonies, detailed

Extract from "The Cambridge Mozart Encyclopedia" by Cliff Eisen & Simon Keefe

Description of all movements of the Symphony #40

NOTE 1)

An interesting, if a tag preposterous,

comment by Jeffrey Lipscomb , found on

amazon:

best interpreters for Mozart's symphonies, detailed.

The special challenges of Mozart's symphonies defeat all but a very few conductors.

Excellent ensemble is required - which eliminates most "budget" offerings. Excessive

speed and hyper-fierce attack must be avoided (goodbye Toscanini, Reiner, Solti and Karajan).

There should be a certain degree of humor and wit (adios to Davis, Fricsay, Krips and Tate).

Charm and grace are essential (exit Bernstein, Harnoncourt and Mackerras). Being brusque or metronomic

is a no-no (pace Klemperer). The playing must be rhythmically secure and avoid bathos (farewell Walter,

despite lovely moments). Above all, Mozart requires passion and conviction, which takes out the

sterile Marriner. The latter's execution is immaculate, but so is the conception.

While I prefer to hear Mozart from a variety of conductors, this Bohm effort strikes me as the

finest current "complete" set. However, Bohm is out-classed in several symphonies by individual

accounts from other conductors.

Here is a brief summary. Abbreviations used: BPO (Berlin Phil), BSO (Boston Sym), CPO (Czech Phil),

CRS (Cologne Radio), DPO (Dresden Phil) DSRO (Danish State Radio), LPO (London Phil), LSO (London Sym),

MCO (Moscow Chamber Orch), NCO (Netherlands Chamber Orch), NPO (Netherlands Phil), PO (Paris Opera),

RPO (Royal Phil), SCO (Saar Chamber Orch), SR (Suisse Romande), VPO (Vienna Phil), VSO (Vienna Sym),

and WS (Wintherthur Sym).

#1-22. These works are juvenile efforts: Bohm offers well-played, streamlined accounts.

Otto Ackermann (1909-60) recorded 1-28, 30-31, 38 & 41 (CHS LPs) in 1952-55.

Most were done with NPO, the rest with WS. These are more "gemutlich" than Bohm's,

and they remain my first choice for #1-22.

#23. I prefer Schuricht/DPO (Berlin Classics) and Ackermann.

#24 Scherchen's step-son Karl Ristenpart (1900-69) was a superb Mozartean who recorded #24-26,

28-31, and 34-41 with the SCO on French LPs. He re-did 24, 28 & 34 in stereo (MHS LP - sadly,

I only have the latter). CD reissues are badly needed. I prefer his #24 to both Bohm and Ackermann.

#25. Ackermann & Bohm are excellent.

#26. Koussevitzky/BSO (LYS) is incredibly virtuosic.

#27. Bohm & Ackermann are excellent.

#28. Ristenpart, Maag/SR (London LP), and Ackermann are tops.

#29. My favorite: Szymon Goldberg/NCO (Epic LP). Scherchen/VSO (Tahra) and Koussevitzky/BSO (LYS)

are also great. Bohm is too Walter-ish here.

#30. Bohm's is the best I've heard.

#31. One of Beecham's greatest (RPO on Sony).

#32. Maag/LSO (Decca) is a clear winner.

#33. Erich Kleiber/CRS (Cetra LP) and Carlos Kleiber/VSO (Melodram) are very special.

#34. Ristenpart's is utterly magical. Beecham/LPO (Dutton) and Schuricht/BPO (History) are great,

but both omit the Minuet.

#35. One of Bohm's finest, along with Beecham/LPO (Dutton) and Schuricht/VPO (EMI).

#36. Busch/DSRO (EMI) is superb, as are Scherchen/VSO (Tahra), Otterloo/VSO (Epic LP), Bohm, and

Beecham/LPO (Dutton).

#38. Maag/LSO (London LP) is magnificent. Other greats: Otterloo (w/36), Sejna/CPO (Supraphon),

Ancerl/CPO (Tahra), and Schuricht/PO (Scribendum).

#39. This is the highlight of Bohm's set: superb. My other favorites are Weingartner/LPO (EMI) and

Erich Kleiber/CRO (Amadeo LP).

#40. Fritz Lehmann/VSO (DG LP), Scherchen/VSO (Tahra) and Beecham/LPO (Dutton) are my favorites.

#41. Barshai/MCO (Melodiya LP) is a cut above Bohm. I also like the slightly fussy Beecham/LPO

(Dutton - NOT his heavy EMI version), Schuricht/PO and Ackermann.

Unfortunately, many of these are out of print or hard to find. So here's wishing you happy

hunting and many hours of delightful Mozart listening!

NOTE 2)

Extract from "The Cambridge Mozart Encyclopedia" by Cliff Eisen & Simon Keefe,

Cambridge University Press (ISBN 0521856590, 2006) that

we have found on the web searching for the "easy target":

About #25_K183: "K183, typically acknowledged as a milestone in

Mozart's

symphonic output for its concentrated intensity and its status as his first

minormode work in the genre (and sometimes referred to as the 'Little' G minor

Symphony to distinguish it from No. 40 in G minor, K550), is especially striking

[for boasting large wind sections and prominent roles for

constituent members]. Scored for four horns as well as two oboes, two bassoons

and strings, it contains numerous engaging instrumental effects. The main

theme at the beginning of the first movement, for example, is replete with

standard Sturm und Drang characteristics, such as syncopation, frenetic activity

and dotted rhythms all at a forte dynamic, but is completely transformed in

the restatement and continuation. Here, the oboe floats mellifluously in

semibreves over accompanimental material in the strings and horns, aligning the

highpoint of its melody (bbemoll) both with the low point in the cellos/basses and

with a moment of gentle harmonic intensification (German augmented sixth).

Later, in the final two bars of the development section, the oboes and four horns

play a crescendo in semibreves from piano to forte unaccompanied by strings

for the only time in the movement, thus carrying by themselves the important

structural responsibility of directing the music towards the recapitulation."

About #40_K550: "The G minor Symphony, K550, stands alongside

the string quartet K421

(1783), the piano concertos K466 (1785) and K491 (1786) and the string quin-

tet K516 (1787) as Mozart's finest minor-mode instrumental work. But unlike

K421, K466 and K516, Mozart's unremittingly intense finale continues in the

minor right up until the final chord. The high esteem in which the work is held

by the musical public at large originated at the beginning of the nineteenth

century; issues of the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung praise K550 as 'a true

masterpiece' (1804), 'Mozart's symphony of all symphonies' (1809) and a 'classical

masterwork' (1813). Not the least of its qualities are the intricate, idiomatic

writing for winds - in evidence throughout - and the passages of harmonic

audacity, such as at the beginning of the development sections of the outer

movements."

About L'oca del Cairo: "

L'oca del Cairo, K422 (The Goose of Cairo) (1783-4). Early in 1783, Mozart was on

the lookout for a new opera libretto; Joseph II had just established an opera

buffa troupe in Vienna and Mozart was eager to show himself equal to the

challenge of Italian comic opera after the success of Die Entfuhrung aus dem

Serail (1782). Searching for a suitable subject, he worked his way through

more than a hundred texts sent to him from Italy. Finding nothing that inspired

him, however, Mozart eventually resolved to request a brand-new libretto from

Giovanni Varesco, the chaplain to the Archbishop of Salzburg; the result

was the ill-fated project L'oca del Cairo, an unfinished opera buffa that survives

only as a fragmentary first act.

Varesco had collaborated with Mozart before, on the opera seria Idomeneo,

commissioned in 1780 by the Munich court. That Varesco had been resident

in Salzburg had given Mozart ample opportunity to intervene in the design of

the libretto during the early stages of its composition; with the constant help

and mediation of his father, Mozart likewise became closely involved in the

creation of the text of L'oca del Cairo. Indeed, Mozart's constant tinkering with

the libretto for Idomeneo had caused considerable friction between the

composer and the poet, and one can surmise that the composer's rather demanding

attitude, coupled with Varesco's own shortcomings and relative inexperience

as a librettist, were contributing factors in the premature demise of L'oca del

Cairo. It certainly does not seem that the difficult experience of collaborating

on Idomeneo with Varesco had diminished Mozart's self-assurance: on 21 June

1783, he wrote to his father that Varesco 'must alter and recast the libretto as

much and as often as I wish'.

An important letter of 7 May 1783 makes Mozart's specifications for his new

libretto quite clear. He wanted the text itself to be absolutely new and by no

means an adaptation of an older libretto - above all, something 'really comic'.

He further stipulated that there be two substantial female roles of more or less

equal importance, one of which should be serious, the other light-serious or

'mezzo carattere', as it was sometimes called; any other female parts and all of

the male roles could be 'entirely buffa' if the plot required it. The following June,

in response to the composer's commission, Varesco sent Mozart a synopsis of

L'oca del Cairo.

Although Mozart was moderately pleased with the opera to begin with -

unlike Varesco himself, who began to express doubts about the quality of his

work almost as soon as it was on paper – it rapidly became clear that certain

elements of the plot needed to be curtailed or altered, while others needed to

be removed altogether. Indeed, most modern critics agree that Varesco's rather

inexpert handling of the story was foremost among the reasons for the failure

of the entire project. Without a doubt, the storyline that survives is a rather

scrambled concoction, although recent research by J. Everson has helped to

clarify some of its more outlandish details, not least the eponymous goose.

Indeed, because the opera remained unfinished, there is no single 'plot' to

speak of, especially since the original synopsis that Varesco sent to Mozart

and the scraps of surviving libretto appear to diverge a great deal. Suffice it to

say that the story concerns an old nobleman, Don Pippo, whose wife has fled

into exile and spread rumours of her death owing to her husband's persistent

ill-treatment, and lives in disguise on the other side of the city. Don Pippo,

thinking himself a widower, resolves to remarry a young friend of his daughter's,

at the same time compelling his daughter to marry an old count. Since

the two unfortunate young women already have lovers, the tyrannous nobleman

imprisons them in a high-walled garden, although he loses no time in

challenging his daughter's young suitor Biondello to enter the garden and woo

her (helpfully setting the time limit of a year). Surprising as it may seem, this

complicated set-up is merely the backdrop for the story. The action within the

opera itself concerns Biondello's plan to breach the walls of the garden with the

help of Don Pippo's wife - a ridiculous scheme to approach Don Pippo's palace

concealed within a giant mechanical goose. The action of the fragmentary first

act as Mozart set it is, however, thoroughly confused by a lack of any reference

to the back-story and much superfluous detail relating to servants and other

minor buffo characters. J. Everson has argued that the peculiar element of the

goose from Cairo (about which Mozart perhaps understandably had his reservations)

derived from a distant model for Varesco's libretto – a novella from the

romance Il mambriano by Francesco Cieco da Ferrara, parts of which continued

to circulate as cheap pamphlets in Italy and Austria even into the nineteenth

century.

As it stands, almost all of Mozart's music survives only in a skeletal form -

as melody and bass-lines, with important instrumental parts also added. Aside

from a few unfinished scraps, there survives an opening A major duet and a pair

of arias with a light, buffo character. Mozart also completed the barest outline

of a D major aria for Don Pippo, an E flat quartet for the two imprisoned women

and their young lovers, and a large-scale finale that begins and ends in B flat.

The fullest part of the surviving score did not come to light until the middle of

the twentieth century, however - a more or less completely orchestrated setting

of Don Pippo's aria 'Siano pronte alle gran nozze', which unexpectedly becomes

a trio (including the two servants Chichibio and Auretta) at roughly the point at

which the other sketch of the piece breaks off. The trio had been in the collection

of the Bavarian-born composer Johannes Simon Mayr (1763-1845); it seems to

have come into his possession through Constanze Mozart at some time in

the early years of the nineteenth century.

In a letter dated 10 February 1783, Mozart informed his father that he was

putting aside his opera in order to work on more profitable projects; there is

no indication that he considered the opera a lost cause at this stage; indeed,

it seems clear that he believed that he would eventually return to it. Of course,

this might have been wishful thinking, or perhaps the reluctance of a son to

disappoint his father, who had been closely involved in the project from the very

beginning. As it is, L'oca del Cairo survives only as a record of Mozart's abortive

first attempts in the world of Italian comic opera.

Nicholas Mathew

Bibliography:

J. Everson, 'Of Beaks and Geese: Mozart, Varesco, and Francesco Cieco', Music & Letters

(1995), 369-83

W. Mann, 'The Operas of Mozart' (London, 1977), 322-30

H. Redlich, 'L'oca del Cairo', Music Review 2 (1940), 122-31

"

NOTE 3)

Description of all movements of the Symphony #40

From:

Wolfgang Amedeus Mozart, sa vie musicale et son oeuvre,

Essai de Biographie critique, par G. De Saint-Foix,

ed. Desclée de Brouwer 1939

Vol.IV: L'épanouissement 1784-1788, pagg.349-355

Symphonie 40, K 550

Symphonie en sol mineur, pour deux violons, deux altos, violoncelle et basse, une flûte,

deux hautbois, deux bassons et deux cors. Comme pour la précédente symphonie, la date

portée ci-dessus marque le moment de l'achèvement de l'oeuvre magnifique qui va nous

occuper maintenant.

L'orchestre comportait primitivement, outre le quatuor des cordes (les violoncelles étant

distincts des basses), une flûte, deux hautbois, deux bassons, et deux cors. Mozart, plus tard,

a remplacé la partie des deux hautbois par deux clarinettes, auxquelles viennent encore s'adjoindre

les deux hautbois, mais avec une partie modifiée: il n'y a ni trompettes ni timbales. Comme on

le voit, l'orchestration primitive devait procurer une saveur plus acide et plus incisive,

un timbre plus "vert", dirait-on volontiers, par suite de la primauté du rôle de ces deux

hautbois.

Sans aucune introduction, Mozart entre dans le vif du sujet, hâtif et inquiet. Seuls, les

violons exposent le thème, se détachant sur un accompagnement des altos divisés; à la deuxième

exposition du thème, les "vents" inscrivent des tenues surmontant celui-ci, et la suite du

premier sujet, forte, en si bémol, fait l'office d'un second sujet où se montre aussitôt

l'ardeur enflammée qui inspire l'couvre tout entière.

Après une mesure de pause, l'atmosphère change et le véritable second sujet, piano, sujet

qu'empreint tout le charme mozartien, s'expose aux cordes seules; la réponse est faite par

les hautbois et les clarinettes, mais lorsque se répète ledit second sujet, il y a interversion

du rôle des instruments. En effet, le voici exposé cette fois par les "vents", auxquels répondent

les cordes. Une énergique ritournelle débutant piano, en ré bémol, ramène en coda le rythme

du premier sujet, qui se répète deux fois pour conclure dans le ton de si bémol, après une brillante

ritournelle s'achevant à l'unisson. On sent en tout ceci, après l'accalmie du second sujet, couver

un feu intérieur que rien ne pourra plus calmer.

Avec une brusquerie géniale, débute l'un des développements les plus originaux de Mozart et,

ajoutons-le hardiment, l'un des plus beaux de toute la musique instrumentale! Un même accord qui

figurait, isolé, avant les barres de reprise, est de nouveau arraché, deux fois de suite, par

l'orchestre entier, et sert à ouvrir le développement: ces deux accords répétés ont suffi à amorcer

le ton le plus éloigné (fa dièze)! C'est donc - dans cette dernière tonalité que, sous les tenues

des "vents", se dessine le thème initial: le voici qui module et s'étend sous un dessin très

énergique et nouveau des violons; il reparaît ensuite, grondant aux basses, dans le ton de mi

mineur. Les dessus er les basses, dans une puissante et somptueuse amplification, se renvoient

le sujet et le dessin qui le suit, et l'on assiste, émerveillé par leur alternance, aux phases

diverses du combat.

Mais ce dialogue - ou plutôt ce duel, - va persister: le sujet demeure cantonné aux seuls violons,

et les "vents" leur opposent en contrepoint une réponse modulée. Ces derniers, bientôt, font

revenir en arrière, ou plutôt retournent sur elles-mêmes les deux premières croches du thème.

C'est ici que semble s'ouvrir maintenant un nouveau combat: le dessin initial du thème, comme

laminé et trituré, fait l'objet d'un échange en mouvements contraires entre les dessus et les

basses, an milieu de modulations chromatiques. Tout à fait à découvert, les "vents" présentent

une transition destinée à ramener la rentrée et les modulations chromatiques donnent audit

passage une expression poignante. Ces quelques lignes tâchent à traduire ce que nous nommons le

premier développement qui, on le voit, demeure strictement thématique.

Voici la rentrée: elle est, d'abord, pareille; mais la suite du premier sujet va donner lieu à

une nouvelle lutte que l'on peut considérer, à bon droit, comme l'aliment d'un second développement

contrapuntique, entre les dessus (premiers violons) et les basses, tandis que les seconds violons

continueront à moduler leurs vigoureux dessins en croches; nous aurons même l'impression que cette

suite du premier sujet a remporté la victoire, lorsqu'elle reparaîtra dans le ton principal.

Ici encore, le second sujet revient, séparé de ce qui le précède, par une mesure entière de pause;

son expression est beaucoup plus intense, puisque nous le retrouvons en sol mineur, et sa suite se

trouve allongée expressivement.

Le résumé psychologique de ce morceau, dont l'impuissance de nos lignes ne peut pas plus évoquer

la force que la délicatesse, se condense dans une coda, non séparée du reste par des barres de

reprise: cette coda se base sur le début du thème initial et parvient, en quelques mesures, à

évoquer toute l'expression contenue dans ce premier morceau. C'est l'expression d'une énergie qui

prend, lors des dernières pages, un caractère d'exaltation farouche, pour céder, à la fin, à un

sentiment de lassitude et de résignation, processus sentimental à peu près constant dans les grandes

oeuvres de Mozart.

Ainsi que le constate ici H. Abert, le double contrepoint joue dans cette symphonie un rôle fort

important: on peut dire que de toutes ses forces, il agit et offre un caractère particulièrement

dramatique, tellement que peu de développements mozartiens sont pénétrés d'une telle énergie animatrice.

Cette constatation du musicologue allemand répond pleinement à la réalité: nous y ajouterons simplement

que ce double contrepoint aboutit à un double développement dans le cours de ce premier morceau, à

la grande différence de ce qui a lieu dans la précédente symphonie.

Notre ambition de décrire l'Andante (en mi bémol) dépasse toutes les velléités; car cet andante a

quelque chose d'indicible qui lui donne son sens véritable. Nous nous rappelons le temps où il nous

faisait l'effet d'une énigme redoutable! Aujourd'hui, la nudité austère de son début nous fait songer

à Bach: cette entrée en imitations du thème qui, à son début, ne paraît être qu'un accompagnement,

forme, pour nous, une annonce qui promet autre chose... Et cette annonce recèle bien complètement

les quatre notes d'un thème qui semble avoir hanté Mozart presque toute sa vie, et que nous retrouverons

comme magnifié et donnant toute sa mesure dans la fugue qui achève sa dernière symphonie, la suivante.

Au second exposé du thème initial, les violons font planer très haut un chant qui se dessine au-dessus

de ce rythme scolastique; alors, la suite du premier sujet passera à la basse, et de cette même suite,

s'envolera un dessin ascendant, fait de deux triples croches isolées lequel sillonnera le morceau tout

entier, s'élevant ou s'abaissant dans le ciel, tel un vol d'oiseaux. Le dessin, comme essaimant dans

les airs, montera donc ou descendra, entourant de son vol la phrase mélodique qui, dans le ton principal,

achèvera cette double exposition du premier sujet. Remarquons, dans tout l'andante, l'importance

croissante du rôle des basses, qui s'amplifiera encore davantage dans l'andante de la symphonie suivante.

Comme dans le premier morceau, qui, d'ailleurs, offre maints rapports de concordance avec notre présent

andante, le second sujet, ici, est isolé de ce qui le précède : attaqué forte en si bémol, il est suivi

d'une réponse qui est faite au moyen du dessin précité, s'échappant de la flûte et des hautbois, pour

conclure en fa majeur. Le thème initial, aux cordes, réapparaît, toujours contrapuntique, dans le ton

de ré bémol; à partir d'ici, les modulations prennent un caractère de plus en plus acerbe, qui nous

semble particulièrement "moderne". Au-dessus de l'implacable fixité du thème, ou plutôt du rythme initial

du morceau, les "vents" se mettent à égrener, en un dessin devenu maintenant descendant, les triples

croches aériennes qui semblent de petites nuées aux teintes irisées, flottant ou fusant au-dessus de

ces sombres profondeurs. H. Abert voit dans ce dessin aérien un motif qui n'interrompra rien, mais, au

contraire, aura un rôle constructeur, et prendra même la direction du discours musical. Mais l'atmosphère,

au cours du développement sera trop troublée pour que ces vapeurs sentimentales l'allègent!

Puis, une cadence forte, dans le ton de la dominante, est suivie d'une réponse imprévue et naÏve, qui

étonne un peu, après ce lourd et angoissant problème sonore: H. Abert y trouve une ressemblance avec

l'appel solitaire d'un rossignol. Nous y reconnaissons surtout la divine simplicité mozartienne qui,

après les problèmes les plus abstrus, trouve telle inflexion, généralement si touchante, que notre primitive

surprise se change en attendrissement! Mais, les modulations qui suivent. aussi rudes, aussi hardies que

les précédentes, donneront, par contraste. un caractère plus angélique ou plus mozartien à la ritournelle

finale de la première partie, que le quatuor et les "vents" se partagent.

La profondeur expressive du développement demeure, à notre sens, quasi unique: le rythme du premier sujet

de l'andante y est frappé à l'unisson sur un do bémol, effet qui, chose bien rare pour des procédé

purement instrumentaux, a été décrit littérairement. A ce rythme obstinément grave et pesant, va

s'adjoindre, tantôt s'échappant des instruments à vent, tantôt glissant sur les cordes, le dessin

en triples croches qui, nous l'avons dit, survole tout l'andante: il parconrra jusqu'à son aboutissement

dans le ton de la dominante d'ut mineur les tons les plus variés; et c'est d'abord par une gamme

chromatique descendante qu'il se chargera de ramener dans ce ton d'ut mineur le premier sujet de

l'andante qui, cette fois, sera attaqué par les "vents". Et sur ce premier sujet va s'échafauder

maintenant un nouveau dessin chromatique, d'allure élégiaque, tout à fait wagnérienne, et ultra-expressive;

il a un caractère si moderne et si poignant, dans sa briè veté, que son rôle ne pouvait se borner à

celui d'une simple transition destinée à ramener la rentrée: Mozart l'a si bien compris qu'il le fait

reparaître au cours de celle-ci, en lui donnant un tour peut-être encore plus expressif.

Ces éléments qui donc ont figuré dans le développement si remarquable de l'andante, reparaissent au

cours de la rentrée: et celui que nous venons de signaler n'est qu'une transposition de la seconde

mesure du thème initial. A partir de la rentrée du premier sujet dans le ton de sol bémol, où se reproduisent

les audacieuses modulations de la première partie, les changements qui existent ne résultent plus, en

général, que de la transposition de ces éléments dans le ton principal du morceau. Que pouvons-nous

dire de cet approfondissement, de cette modernisation de toute cette rentrée, sinon que Mozart y a

intégré les dernières conquêtes de son art et de son style? Les deux termes rassurants de Menuetto

allegretto ne répondent en rien, pour nous, à la lutte âpre et sans merci qui reprend dans ce menuet:

nous atteignons au paroxysme de la tension nerveuse, traitée par une utilisation volontaire de la rudesse

contrapuntique des vieux maîtres. Par deux fois, le contrepoint se renouvelle en se resserrant pendant

la seconde reprise du menuet : ce thème attaqué par les basses, après les barres de reprise, va descendre

par échelons, tandis que les dessus l'étireront avec violence vers les hauteurs, et voici que, après de

rudes accords conclusifs, les premières mesures du thème exposées piano à découvert, par les "vents",

glissent apaisées, et affirment ainsi le caractère élégiaque de la symphonie entière! Surprise merveilleuse,

et dont l'intime résignation n'est réellement qu'à Mozart.

Quelle unique et charmante éclaircie que celle du trio majeur! Quel repos, quelle douceur idyllique règne

ici! Les courbes charmantes du thème sont dessinées par les cordes, auxquelles succèdent les a vents s qui

leur répondent; l'épisode élyséen de la seconde partie de ce trio, avec sa grâce et sa pureté, nous

fait momentanément oublier la tragique aventure que dépeint toute la symphonie. De nouveau, comme dans

le premier menuet, les "vents" seuls dessinent la dernière période, créant ainsi le lien d'une profonde

unité entre les deux menuets, - ou plutôt entre le menuet et son trio; ces "vents", accusent le

caractère viennois; ou allemand du Sud de la danse, auquel les cors ajoutent la magie du coloris

romantique, tout voisin de Schubert.

Les principales phases du premier allegro vont se retrouver dans le finale Allegro assai; mais, sauf

pour ce qui est du second sujet correspondant avec symétrie à celui du premier morceau, le caractère

élégiaque du premier allegro disparaît ici, étouffé par une hâte fougueuse et endiablée, qui

enflammera aussi bien tous les thèmes que tous les traits de ce finale.

Le thème, muni de son refrain, est contenu entre des barres de reprise, donnant lieu à une double